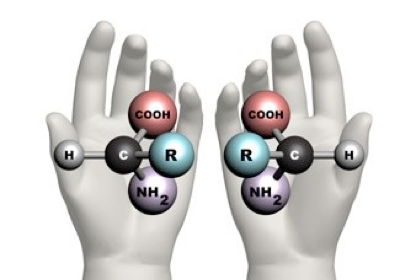

The word ‘chiral’ comes from the Greek word, kheir, which means ‘hand’. An object is said to be chiral if it cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. For instance, your hands are chiral. If you place your right hand over your left hand, it doesn’t fit – the thumbs stick out in opposite directions. And when you turn your hands to point them in the same direction the palm of your hand still looks different to the back of your hand.

Chirality is all around us, The easiest chiral objects to spot are those that are spiralled, such as shells, horns, springs, spiral staircases, vines and so on. Some chemicals are chiral too, such as DNA, sucrose and carvone. Examples of how different chiral structures interact differently with the body are those that have an odour or taste. You can smell and taste things because you have receptors that pick up the smelly or tasty chemicals. The classical (and historically first) example of how different chiral forms interact via smell was carvone. One enantiomer smells of caraway seed whilst the other enantiomer smells of spearmint.

In this film The Oxford Sparks team and Oxford Mathematician Alain Goriely go to the Museum of Natural History in Oxford to explore chirality, its uses and its part in explaining the shape and possible alternatives to our universe.