When Ann Mitchell was called up for war service in 1943 in the Foreign Office, she had no idea what kind of job she was accepting. The Oxford Mathematics graduate spent the next two years at Bletchley Park, cracking the secret Enigma messages sent by the Germans in the Second World War. It was the beginning of a remarkable life.

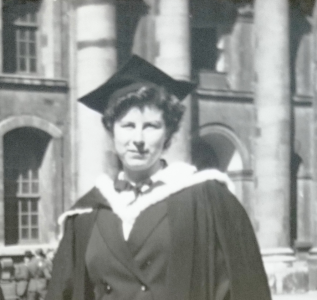

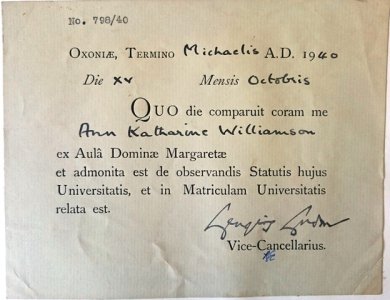

Born and brought up in Oxford, Ann won a scholarship to Headington School for Girls, where she showed an aptitude for maths despite being discouraged: “My headmistress firmly told my parents that mathematics was not a ladylike subject,” she recalled. “However, my parents overruled her and I pursued my chosen path.” Thanks to her enlightened parents she was one of only five women accepted to read maths at Oxford University in 1940.

University in wartime had its privations, particularly in winter as her room in Lady Margaret Hall was heated by an open fire but, due to rationing, there was only enough coal for one day and one evening a week. However, Ann thrived, helping in the war effort and swimming for the University. She graduated in mathematics from Oxford in 1943 and the University Appointments Board sent her to a place called Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, to become a temporary assistant in the Foreign Office.

Ann was assigned to the brick-built Hut 6 Machine Room. The Machine Room was connected to the Watch, which was the vital hub around which the whole of Hut 6 dealt with the high priority German army and air force codes, most important of which was the ‘Red’ code of the Luftwaffe. The experts could deduce by the call-signs or radio frequencies from which unit the message had originated and their first task was to make an informed guess about the wording. They wrote out some of the jumbled nonsense which had been received and underneath wrote a ‘crib’ of the probable German text. Ann’s key role was the next step in breaking the code, composing a menu that showed links between the letters in the text received and the crib, with the more compact the menu the better.

Ann and her colleagues in Hut 6, most of whom had degrees in economics, law or maths, worked round the clock in shifts, from 9 am to 4 pm, 4 pm to midnight or midnight to 9 am, with two weeks on each shift and one free day each week. It was relentless and demanding work, yet they never knew (and didn’t ask) where their work came from or where it went to next.

Ann never told anyone, not even her husband, about her wartime role. But in the 1970s the secret was out and Ann was able to tell her story, not least to an avid media. She said: “It was a fillip towards the end of my life, suddenly to have risen in importance, to go from being a nobody to a somebody. A whole past that nobody was interested in and suddenly lots of people are. It’s very strange.” The Enigma codebreakers were formally recognised in 2009 when Ann and other surviving Bletchley veterans were awarded a commemorative badge by GCHQ. “I am proud of what we did,” she said. “It is just a small badge, but it means a lot to me.” Ann and her colleagues are celebrated in Tessa Dunlop's The Bletchley Girls: War, secrecy, love and loss: the women of Bletchley Park tell their story, Hodder and Stoughton, 2015.

Her ground-breaking research led not only to an MPhil from Edinburgh University, it also prompted changes to Scottish law which ensured that the needs of children were properly taken into account in a divorce settlement. Her first book ‘Someone to Turn To, Experiences of Help before Divorce’ (1981), examined where recently divorced people had sought or received help when their marriages had broken up, exposing substantial dissatisfaction with Scottish legal procedures. She was particularly concerned that the needs and feelings of children were often ignored, and her seminal work ‘Children in the Middle’ (1985) documented this poor state of affairs and gave considerable impetus to the use of mediation in family cases.

Having published several books on divorce, aimed not just at researchers but also at parents and the children themselves, her writing took a new tack with two acclaimed local history books on Edinburgh, ‘The People of Calton Hill’ (1993) and ‘No More Corncraiks’ (1998). Then at the age of 89 she published a biography of her mother, Winifred.

In 2019 Ann was part of the Forgotten Women of Oxford Computing Project led by Ursula Martin which celebrated the until now hidden history of Oxford women's pioneering role in the development of computing. Ann's son Andy told Ursula that his mother "was delighted, not to say flattered, that she is still remembered.” She shouldn't be, even if it took us all so long.

Many thanks to Andy Mitchell for providing much of the material for this obituary.