Logarithms Solutions

Part of the Oxford MAT Livestream.

Revision Questions

- (23)4=212. (24)3=212. 2423=27. 2324=27.

- This is a quadratic for 1x with solutions 1x=−1 or 1x=−3. So x=−1 or x=−13. Alternatively, we could multiply both sides by x2 and solve the quadratic that we get.

- This is log1012.

- The quadratic inside the brackets factorises, and this is log3(x+2)+log2(x+1). Other answers are possible, such as log3(2(x+2))+log3((x+1)/2).

- The left-hand side is just 2 so we want 2=x3. So x=3√2.

- The left-hand side is 1+logx2 so we want logx2=2. So x2=2 and x=√2 (not −√2 because we're told that x>0).

- Take (x+5) to the power of each side to get 6x+22=(x+5)2. Expand the square and rearrange for x2+4x+3=0. The solutions are x=−1 or x=−3. Check these solutions; log4(16)=2 and log2(4)=2.

-

- ln1024=ln(210)=10ln2=10a.

- ln40=ln8+ln5=3a+b.

- ln√2/5=12ln2/5=12(a−b).

- ln(1/10)=−ln10=−ln2−ln5=−a−b.

- ln1.024=ln1024+ln1/1000=10a+3(−a−b)=7a−3b.

- There are other solutions, partly because b=a×log25.

- ex+y+ey−x−ex−y−e−x−y+ex+y−ey−x+ex−y−e−x−y. That's 2ex+y−2e−x−y.

ex+y+ey−x+ex−y+e−x−y+ex+y−ey−x−ex−y+e−x−y. That's 2ex+y+2e−x−y. - 2x=3 is what it means for x to be log23.

If 0.5x=3 then 2−x=3 so x=−log23. Alternatively, just write down x=log0.53.

If 4x=3 then 22x=3 so x=12log23. Alternatively, just write down x=log43. - 1x=1 is true for all real x. 1x is never equal to 3 for real x.

- 0b=0 for any real b>0. a0 is never 0.

- We have log10x=106, which is a million. So x is ten to the power of a million. That's got a million zeros at the end.

- Multiply both sides by ex and rearrange to get e2x−4ex+1=0. This is a quadratic for ex. Solve it for ex=2±√3. So x=ln(2±√3).

Following the previous working, we can see that we'll get two roots for ex if c2−4>0. But we need these to be positive roots, so we need c>2. If c=2 there's a repeated root. If c<2 there are no roots. - Move both terms onto the left-hand side and use the fact that (N+√N2−1)(N−√N2−1)=N2−(N2−1)=1; that's the difference of two squares. Remember that ln1=0.

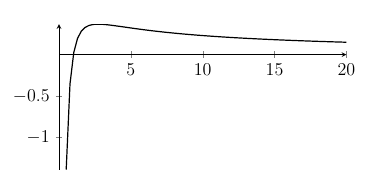

As a result, our solutions above x=ln(2±√3) are actually x=±ln(2+√3), revealing a lovely symmetry. But you could have spotted that from the equation, of course! - We have ln(xy)=ln(yx) which we can simplify down to ylnx=xlny. Now rearrange to get lnxx=lnyy. You might choose to put this fraction the other way up, or to square both sides or something, so your f(x) might not be the same as mine. Here's a sketch of y=ln(x)x.

- This is (alogab)k=bk.

- We can use a similar bit of algebra to the previous question with k=logbc.

ax=alogablogbc=(alogab)logbc=(b)logbc=c.

So ax=c and therefore x=logac. - If we relabel the previous result, we can write logcalogab=logcb. Now divide by logca to get

logab=logcblogca

In particular, if we take c to be the number e, then we can write that fraction with ln instead of loge. This is handy because it shows that we can always write logarithms like logax in terms of ln. All other logax graphs are just simple transformations of the lnx graph.

MAT 2007 Q1I

If we make the substitution x=log10a and y=log10b then it's easier to see what's going on.

4x2+y2=1

We want to make a large, which is the same as making x large (because log10x is an increasing function).

But we have x=±12√1−y2 from the above, which is clearly maximised when y=0 and x=12. Check that this is actually possible; we would need 12=log10a and 0=log10b, so a=√10 and b=1. This is OK.

The answer is (c).

MAT 2008 Q1B

Let x=log10π. Note that 0<x<1 because 1<π<10. The four values are

x,√2x,x−32x.

Now we want to compare these terms. We have x<√2x if x2<2x which happens if x<2. Also x<x−3 because x<1. Also x<2/x because x<√2.

The answer is (a).

MAT 2008 Q1E

Ignore small powers of x inside each pair of round brackets. We get something like

{[(2x6+…)3+(3x8+…)4]5+[(3x5+…)5+(x7+…)4]6}3

Now apply the powers on the round brackets and compare terms again

{[23x18+34x32+…]5+[35x25+x28+…]6}3

Take the largest power inside each square bracket and apply the power on that bracket

{320x160+x168+…}3

Take the largest power inside the curly brackets and apply the power on that bracket

x504+…

The answer is (d).

MAT 2010 Q1E

First note that log48=32 because 4=22 and 8=23, so 43/2=8.

Is log23>32? Only if 3>23/2 so only if 9>8. Yes!

Is log32>32? No, it's less than one.

Is log510>32? Only if 10>53/2, so only if 100>125. No!

So only log23 is larger than 32.

The answer is (a).

MAT 2012 Q1C

Simplify (√3)3=3√3.

Simplify log3(92)=4.

Simplify (3sin60∘)2=(3√3/2)2=274.

Simplify log2(log285)=log2(log2215)=log2(15).

The next thing I notice is that 15<16 so log2(15)<4. Aha, that means that it's less than log3(92).

Then perhaps I could notice that 274>4. So my remaining candidates for the smallest of the numbers are 3√3 and log2(15). But 3√3=√27>4. So option (d) is the only one that's less than 4.

The answer is (d).

Extension

- We've seen above that for 0<α<1, the smallest is (a). For α>1, it turns out that α−3 is the smallest.

- (8!)9=(8!)8×8! and (9!)8=(8!)8×98. Now 98 is clearly larger than 8! (each is the product of eight things, and in the case of 98, each of those eight things is larger!). So (9!)8>(8!)9.