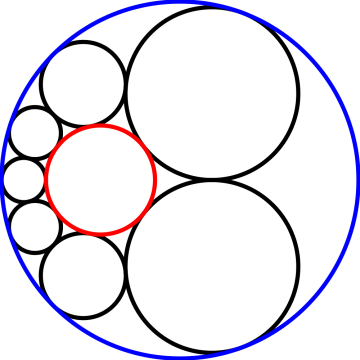

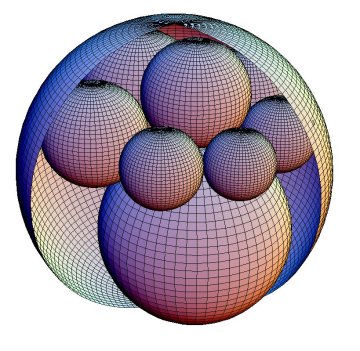

Oxford Mathematician Kristian Kiradjiev has been awarded the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications (IMA) Early Career Mathematicians Catherine Richards Prize 2017 for his article on 'Exploring Steiner Chains with Möbius Transformations.' Here he explains his work.

Oxford Mathematician Dmitry Belyaev is interested in the interface between analysis and probability. Here he discusses his latest work.

"There are two areas of mathematics that clearly have nothing to do with each other: projective geometry and conformally invariant critical models of statistical physics. It turns out that the situation is not as simple as it looks and these two areas might be connected.

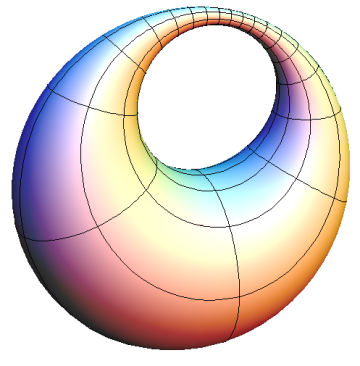

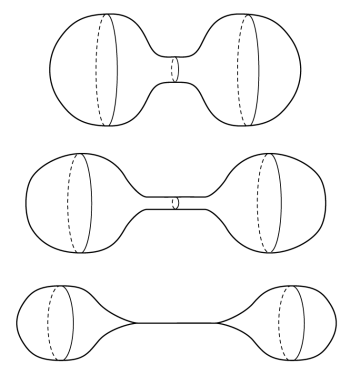

As part of our series of research articles focusing on the rigour and intricacies of mathematics and its problems, Oxford Mathematician Andrew Dancer discusses his work on Ricci Flow.

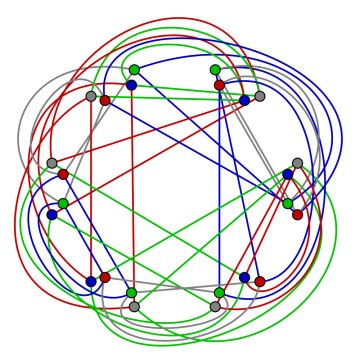

As part of our series of research articles focusing on the rigour and intricacies of mathematics and its problems, Oxford Mathematician David Hume discusses his work on networks and expanders.

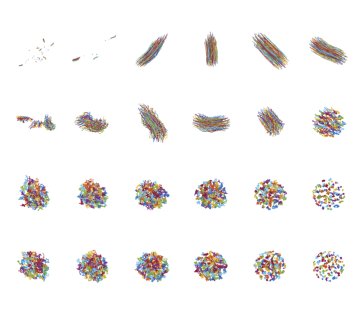

Researchers from Oxford Mathematics and Imperial College London have provided a “'mathematical thought experiment' to inspire caution in biologists measuring heterogeneity in cell populations.

Taxation and death may be inevitable but what about crime? It is ubiquitous and seems to have been around for as long as human beings themselves. A disease we cannot shake. However, therein lies an idea, one that Oxford Mathematician Soumya Banerjee and colleagues have used as the basis for understanding and quantifying crime.

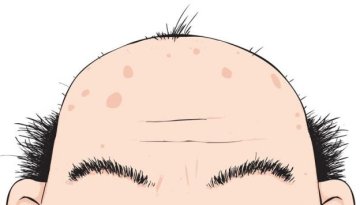

How does the skin develop follicles and eventually sprout hair? Research from a team including Oxford Mathematicians Ruth Baker and Linus Schumacher addresses this question using insights gleaned from organoids, 3D assemblies of cells possessing rudimentary skin structure and function, including the ability to grow hair.

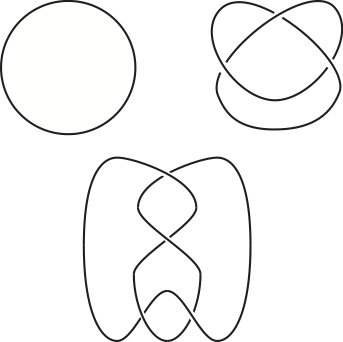

It is an intriguing fact that the 3-dimensional world in which we live is, from a mathematical point of view, rather special. Dimension 3 is very different from dimension 4 and these both have very different theories from that of dimensions 5 and above. The study of space in dimensions 2, 3 and 4 is the field of low-dimensional topology, the research area of Oxford Mathematician Marc Lackenby.

Oxford Mathematician Nick Trefethen was recently awarded the George Pólya Prize for Mathematical Exposition by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM) "for the exceptionally well-expressed accumulated insights found in his books, papers, essays, and talks." Here Nick&n

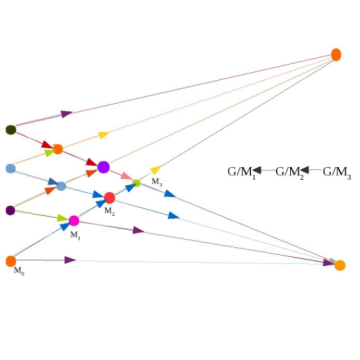

As part of our series of research articles deliberately focusing on the rigour and intricacies of mathematics and its problems, Oxford Mathematician Nikolay Nikolov discusses his research in to Sofic Groups.

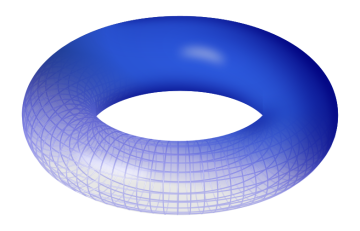

As part of our series of research articles deliberately focusing on the rigour and intricacies of mathematics, we look at Oxford Mathematician Minyhong Kim's research in to the relationship between number theory and topology. Minhyong Kim is Professor of Number Theory here in Oxford and Fellow of Merton College.

It is probably well-known that number theory is the source of some of the oldest and most accessible questions in mathematics:

Governments around the world are seeking to address the economic and humanitarian consequences of climate change. One of the most graphic indications of warming temperatures is the melting of the large ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica. This is a litmus test for climate change, since ice loss may contribute more than a metre to sea-level rise over the next century, and the fresh water that is dumped into the ocean will most likely affect the ocean circulation that regulates our temperature.

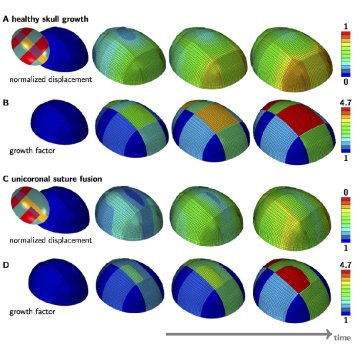

Mathematics is delving in to ever-wider aspects of the physical world. Here Oxford Mathematician Alain Goriely describes how mathematicians and engineers are working with medics to better understand the workings of the human brain and in particular the issue of abnormal skull growth.

Oxford Mathematician Doireann O'Kiely was recently awarded the IMA's biennial Lighthill-Thwaites Prize for her work on the production of thin glass sheets. Here Doireann describes her work which was conducted in collaboration with Schott AG.

Many anticorruption advocates are excited about the prospects that “big data” will help detect and deter graft and other forms of malfeasance. But good data alone isn’t enough. To be useful, there must be a group of interested and informed users, who have both the tools and the skills to analyse the data to uncover misconduct, and then lobby governments and donors to listen to and act on the findings.

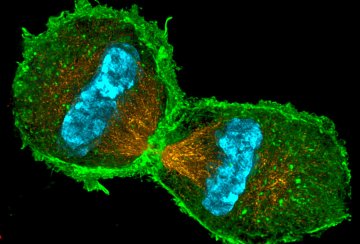

The human body comprises an incredibly large number of cells. Estimates place the number somewhere in the region of 70 trillion, and that’s even before taking into account the microbes and bacteria that live in and around the body. Yet inside each cell, a myriad of complex processes occur to conceive and sustain these micro-organisms.